Introduction — National involvement in open science (OS)/open access (OA)

The Country Cards[1] provide an extensive collection of information regarding the current status of OS at the national level in Europe.

The first and most obvious fact when reviewing these documents is the positive consensus regarding OS by the national authorities in Europe. Indeed, each European state that has been researched, is involved and active in OS, albeit at very different levels. If this information does not allow for more conclusions at this stage, it sends a positive message on the development of OS in Europe.

A more in-depth review can therefore be conducted based on the Country Cards, in order to assess the national strategies in place and the degree of each country’s involvement in OS.

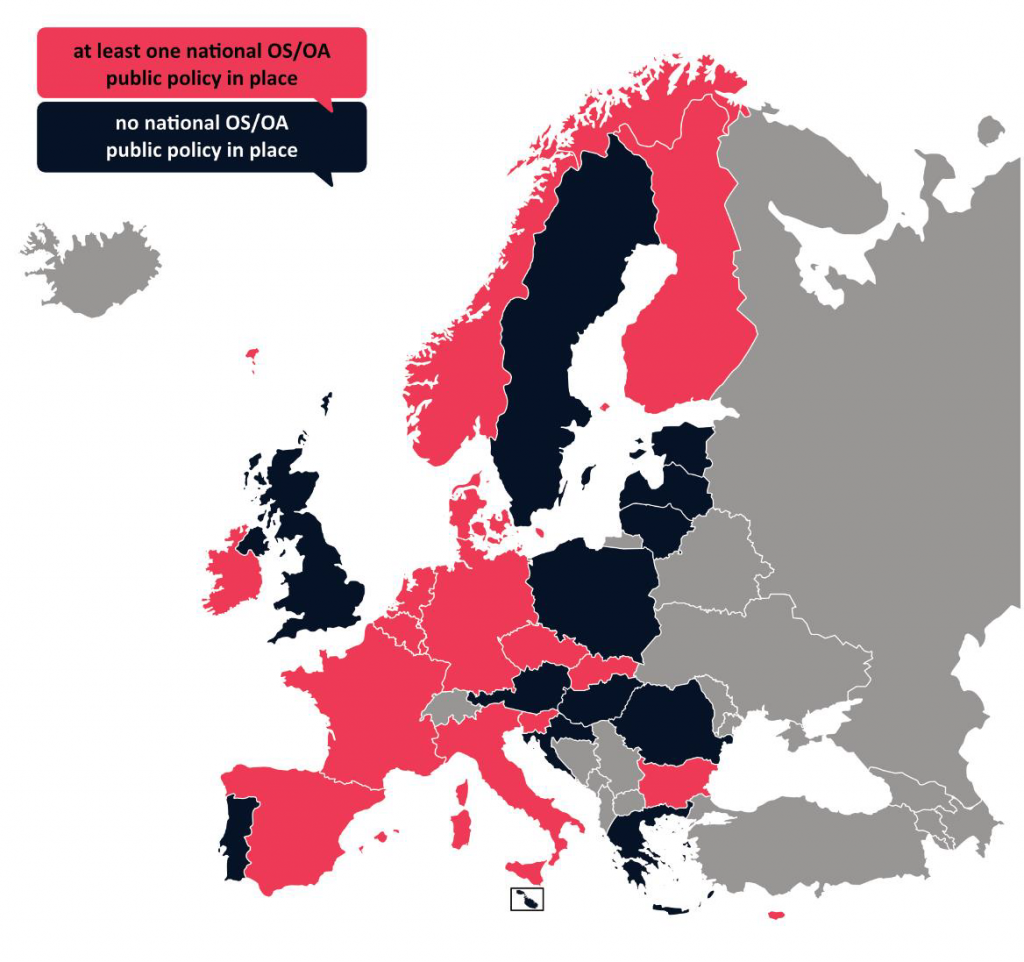

National policies on Open Science & Open Access

Malta map: Malta Map Vectors by Vecteezy

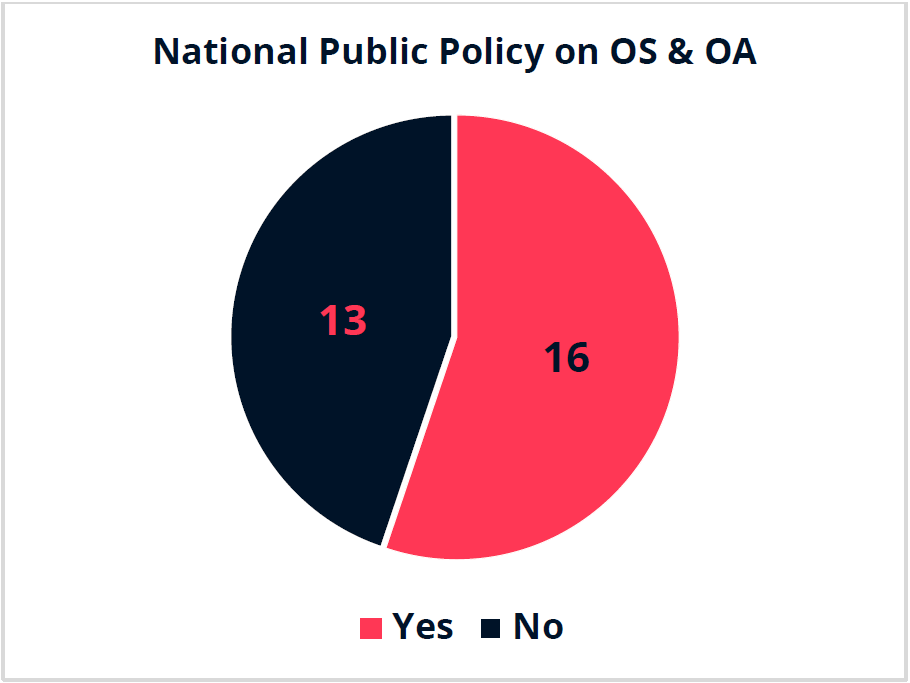

The national OS public policies will be the main material researched as these policies will be selected and analysed in order to flag responsible OS public policies and good practices. The existence of national OS public policies represents the most approachable way to assess the national involvement and support of OS through concrete measures or explicit strategies. It also shows conformity with the EU Directive on Open Data and the Re-use of Public Sector Information (PSI Directive) which calls for the adoption of national policies.

Close to half of the selected countries do have at least one national policy on OS or OA in place as of January 2022. Some countries – Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Bulgaria – have multiple policies in place which either address different focuses (Finland) or present the country´s involvement through time and gradual improvement (France, Czech Republic). These policies exist in a wide range of formats: National Policy, National Strategy, National Plan, National Framework, State Plan, Action Plan, OA Strategy, National Programme, Declaration and degree of mandate – hard or soft.

Nevertheless, as presented in the Country Cards, the lack of existing national OS policies does not mean a lack of involvement in OS initiatives, since all selected countries are active in OS in some ways. This multiplicity of national strategies is particularly clear in cases where OS is more the mandate of research institutions, federal or local authorities, or national research funders rather than national authorities (for instance in Malta where the University of Malta is the most active national institution in OS).

Furthermore, the majority of countries without a national OS public policy in place (Austria, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Latvia, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Sweden) are in the process of planning and/or implementing national policies at the time this report is produced. Thus, this overview and mapping is therefore to be understood as a work in progress, at the time of this report, with most of the existing OS national public policies having been implemented in the last 5 years in Europe (18 out of 22) have been published since 2017.

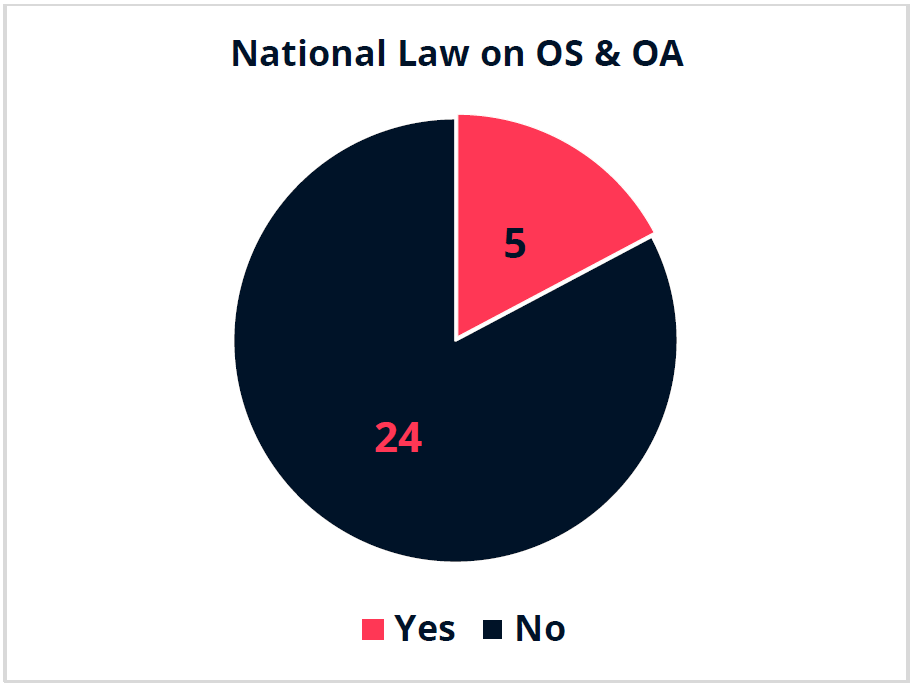

The National Laws regarding Open Science & Open Access can be assessed as a stronger commitment than National Policies due to it being strictly legally binding. The existence of such legislation can as well be perceived as a clear strategical position of the national authorities in favour of a binding approach in order to advocate for, support and implement OS.

The analysis of the Country Cards shows that this kind of strategy is the least adopted by the national authorities with only 5 National Laws established. It must as well be mentioned that OS rarely is the main scope of the national legislation (only one clause of the Belgium Copyright Law addresses OA, for instance).

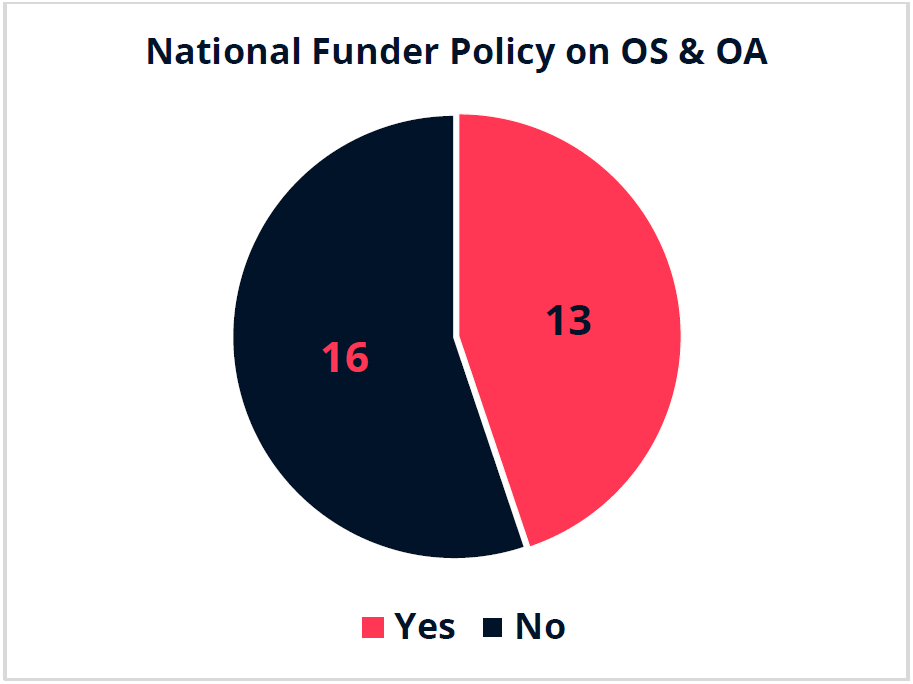

National funder policies on Open Science & Open Access

The national funder policies on Open Science can provide a proof of extended national involvement in OS. These national policies can provide relevant OS good practices, examples and tools (such as the Journal Checkers for the cOAlisionS for instance: https://journalcheckertool.org/).

However this data is to be approached carefully due to the fact that some national funder policies do not implement their own policies but rather use the national OS policies instead, when these ones are relevant.

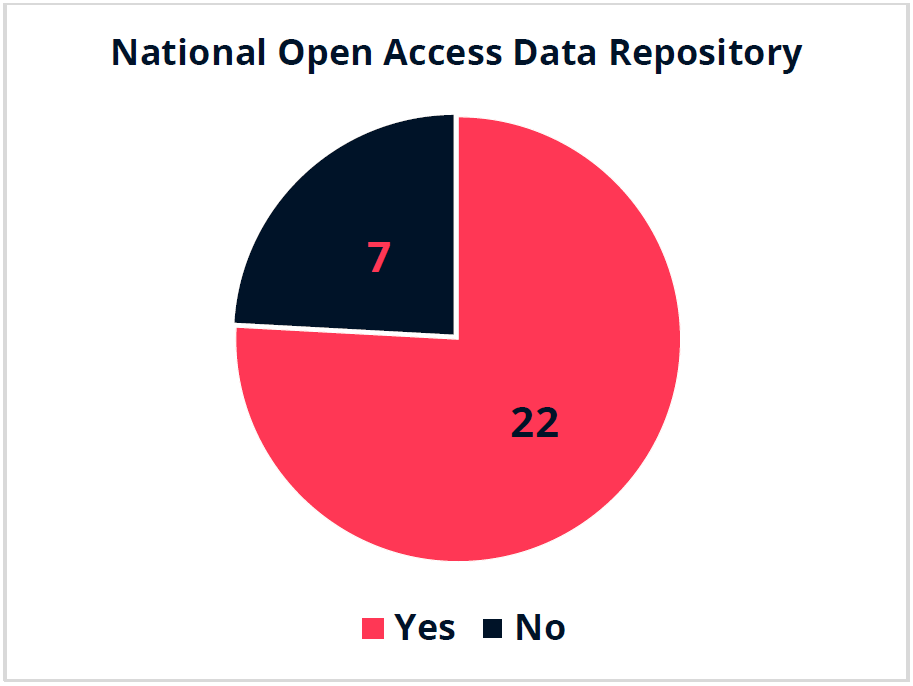

National Open Access Repositories

Having an Open Access infrastructure in place, in particular repositories, is central for a responsible data management environment. The density of OA repositories in Europe is thus widespread.

Nonetheless, these infrastructures, if they are supported and encouraged by the national authorities and OS public policies, are only rarely established and managed by these authorities, but are rather the result of institutional initiatives. This, however, does not stop some of these institutional repositories from gaining a de facto national mandate – in some cases, such as in Malta where the OAR@UM is used by all stakeholders involved in research.

A problem related to this situation remains, as many repositories are focusing on one research field, which can pose limitations for researchers, in particular in the case of interdisciplinary research.

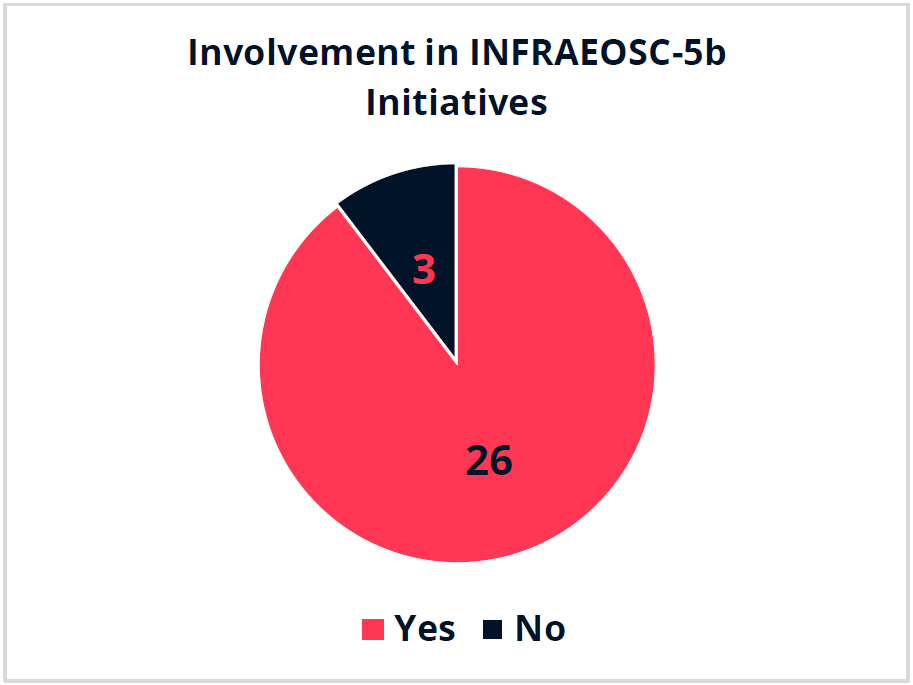

Involvement in INFRAEOSC-5b initiatives

The inclusion of INFRAEOSC-5b initiatives in this research provides a meaningful transnational perspective on OS in a context of growing interconnection and collaboration in Europe under the patronage of the EU.

As a part of the Digital Agenda, the European Commission made public the EOSC Declaration in October 2017 (https://eoscportal.eu/sites/default/files/eosc_declaration.pdf), calling for the creation of the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) as an initiative between the member states, scientific communities, citizens and industry. This multi-disciplinary environment, where stakeholders are able to publish, find and re-use data, tools and services for research, innovation and educational purposed, is thus one of Europe´s main instruments to support OS. EOSC is indeed seen a pilot action to improve the new European Research Area (ERA) and should be articulated with the European strategy for data. Its completion should lead not only to a higher research productivity, new insights and innovation, but also to an improved trust in science.

In this context, the EC launched the INFRAEOSC-5b call, four regional initiatives (EOSC-Synergy, NI4OS Europe, ExPaNDS, EOSC-Nordic) and one thematic project (FAIRsFAIR), aiming at providing support to integrate EOSC-relevant national initiatives in Europe.

The involvement of 26 from the selected countries in INFRAEOSC-5b initiatives sends a clear message of national support to these EU OS initiatives and projects. The involvement of 10 countries in at least two of these initiatives – Germany being the only one to be involved in all – confirms even more this tendency for great national interest for OS regional engagement.

The fact that countries without OS national public policies are also active within the EU OS framework, in particular, proves that the absence of existing national policies does not echo a lack of national involvement in OS. This can however be interpreted as a specific strategy to implement OS where OS policies would be more in the hands of institutions, with the national authorities being focused on international OS initiatives. The involvement in IFRAEOSC-5b´s calls can as well be understand as the national authorities´ first step towards the implementation of OS national policies.

A clear consensus, unlike any other information analysed in these Country Cards, appears therefore when it comes to the European Union´s OS initiatives. The importance of the EU funding initiatives regarding the development and implementation of OS policies in Europe should therefore be highlighted.

[1] For more information on the Country cards see article “Country Cards of open science policies.”

This passage is part of D5.1: Report on existing policies and guidelines written by Mathieu Rochambeau, Teodora Konach.