Challenges for Open Science Infrastructures

Examining the challenges related to research ethics, to research integrity and to the FAIR principles arising for Open Science Infrastructures

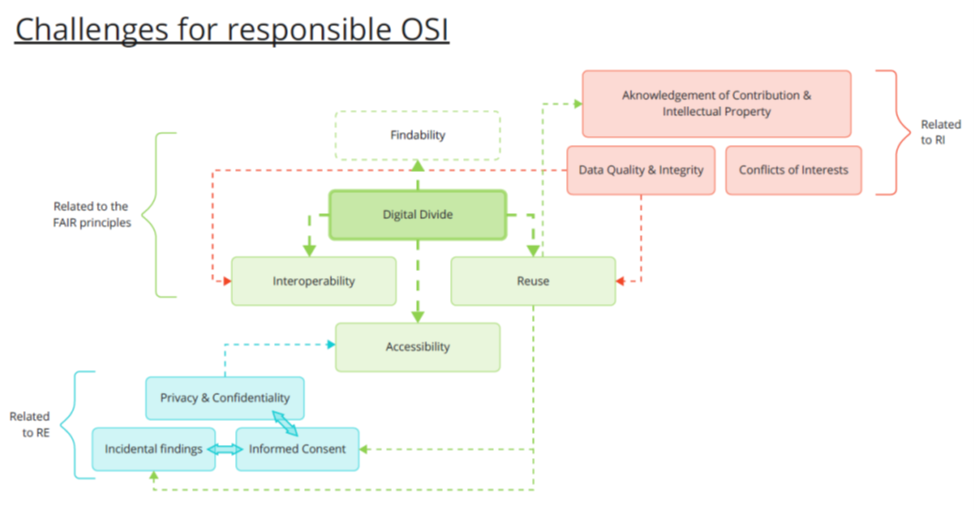

Based on the workshops that took place within the framework of the ROSiE project, the challenges encountered by OS Infrastructures (OSI) were examined. We classified those challenges in three main categories, according to the ROSiE research objectives: 1) challenges mainly related to research ethics (RE); 2) challenges mainly related to research integrity (RI) and 3) challenges mainly related to the FAIR principles. All challenges have RI implications and several challenges are interrelated.

1. Challenges related to research ethics

The challenges mainly related to research ethics (i.e., related to data collected on human subjects) were:

- Incidental Findings can be a challenge for OSI – namely, to find unexpected results and observations in a set of data.

“The whole principle of open data is that you get unexpected results from open data, as people see new patterns that you don’t necessarily see in the first instance. So, giving a consideration on how you do that for really successful citizen science projects is absolutely crucial in my mind[1].”

- Informed Consent: an adequate informed consent (i.e., considered as such by traditional evaluation of research ethics committee) can be challenged by certain OS methodologies. To be transparent enough about all particular uses and re-uses in the context of OS is not always possible, simply because they (especially the re-uses) cannot be envisioned at the time of data collection: in this case, the consent cannot be considered entirely “informed” over the course of the data life cycle.

“Our ethics committees are not equipped to help us with such complicated cases and methodology”

“The complaint about broad consent had been that it kind of limits the tissue donors’ autonomy because the particular uses of the data is not transparent to them”

- Privacy & Confidentiality requirements are a challenge for OSI, namely in limiting the access to data (especially sensitive and personal data). OSI often confront a dilemma between the level of anonymization of open access data and the level of utility and reusability. Privacy and confidentiality requirements may also impair the utility of some support - for example, when limiting the sharing of some information in DMPs:

“I searched for DMP models in order to benchmark how others had addressed these issues. Another important feature [of data sets] is that they often contain private information that cannot be made public. The available DMPs are not always super useful[2].”

This challenge is highly dependent on the nature of data (i.e., sensitive or personal data, digital or physical data) and thus indirectly dependant on the discipline involved. Those limitations are legally grounded in Europe – e.g., with GDPR requirements.

“I think the tagline is ‘as open as possible and as legally as necessary'’”

Privacy and Confidentiality may thus limit data accessibility and reusability if not properly addressed ab initio, which they cannot always be.

2. Challenges related to research integrity

- Acknowledgment of Contribution & Intellectual Property: OS may create situations where the contribution of the person who collected the data may not be recognized in someone else’s discovery, made using this data:

“There’s always this hesitation: that releasing the data, somebody might discover something really interesting and then, you know, you put all that effort in and somebody else gets the Nobel Prize.”

Although this challenge is not specific to OS, the OS context (namely, wider dissemination of data, diversity of possible actors having access to it etc.) can increase the impression of a conducive environment for this issue to occur. This perception is important to be aware of, as it may constitute an obstacle to the opening of data.

Sometimes, what is difficult is to give the appropriate credit to all individuals that contributed to the data collection, for example for historical data:

“So usually, let’s say during a colonial expedition, the scientist were primarily the European scientists, when a lot of local helpers and local experts and local scientific helped them to collect the data. And they’re usually not mentioned. […] So how do you connect those things and find those persons and provide attribution to and give them the credit to that?”

Data curation is one of the 14 types of contribution to research recognized in the CRediT taxonomy[3], but a formalized system is missing to acknowledge the contribution of ‘data curators’ for instance when citing a paper: they are at the best mentioned in a footnote or in the ‘Acknowledgment’ section.

- Conflict of Interests: while not explicitly discussed, this challenge was mentioned in the context of research equipment cofounded by private and public institutions.

- Data Quality & Integrity refers to the question how to guarantee the quality of the data, especially for citizen science data platform (data not collected by professional scientists):

“You have identified a fundamental issue about how you guarantee that the quality of the data is high. And it is an issue that we, as a citizen science community, are going to have to solve if we want to see the scale of our activities growing.”

Part of this challenge is related to data collection and dissemination: to limit missing information and human errors (more likely to occur with a high number of users) and ensure that the data was not fabricated or falsified. Ensuring data quality and integrity is not only a challenge for OS, but OS practices amplify the impact of a lack of quality or integrity by collecting and disseminating data at large – even inaccurate or otherwise unsuitable data.

3. Challenges related to some of the FAIR principles

- Accessibility: data ownership may first challenge accessibility. Data does not necessarily belong to the hosting platforms. It can also belong (depending on the nature of data) to the person, to the institutions or "projects", which can complicate the possibility of free circulation and control of OSI on these data. In the specific case of sharing research papers[4], disciplinary traditions of authorship or copyright may limit open access, for example when visual elements are part of the data to be shared:

“Using images or video to support a discussion implies questions of copyright. Very often, in disciplines like history of art, free circulation of articles and publications is restricted, or it would imply removing images that are fully part of the scientific argument.[5]”

The difficulty for OSI to secure long-term funding can also hamper open access: the underlying question being how to reconcile the requirements of open access with the need for incomes (for example, editor’s incomes). The question of the possibility for open data to be freely accessible (without charging users) has been raised by some participants of the workshops. Access limitation may also differ according to the origin of the funds (public or private) and the specific requirements associated with their use (for example, geographical restriction). A need for guidance and policy in order to ensure the appropriate use of public fund in this situation was raised:

“We have some right concept […] and some proper policies that ensure that we don't waste taxpayers’ money but that we have it used according to the aims that we have and towards what we are supposed to deliver for getting this money that we have from the countries from commission and ultimately from taxpayers. So for me, this is still also a point to consider when you talk about responsible Open Science”.

Finally, some ethical and legal requirements may challenge open access (for example, for sensitive data, see Privacy and Confidentiality).

- Interoperability can raise challenges in a different way, because of the diversity of the disciplines, of the platforms and of the way they are managing data, of practices or even because of cultural diversity. Participants acknowledged the difficulty to create a template that “works for everything”, and the challenge to adapt OSI to the requests of researchers from different domains.

“I mean, we are dealing with a similar situation and our extra challenges is that we were working with 270 different museums across 23 different countries. So everybody has their own local practices and then we have to come up with the European practice and sometimes they don't match.”

“So the main problem there is, as I understand it, is if there was unity of the regulations across countries, there are also some cultural differences. Then how do you implement everything into an infrastructure research that tries to enable some transnational work?”

This challenge is strongly interrelated to the re-use challenge.

- Re-use: while it was recognised that one of the aims of OS is to allow the re-use of data and methods to make results replicable, several participants highlighted challenges in ensuring the re-use of data, including (1) the lack of harmonisation in the way data is collected and stored, (2) the difficulty to ensure data relevance over time and (3) the difficulty to sharing qualitative data in a re-usable format. Another challenge is to ensure that re-use would benefit the communities that initially created the data, or at least that they receive a fair credit for their collective effort.

“So, making it available, you know, more generally, even not to the public, but just to a wider scientific community is not only difficult but also maybe not so meaningful because nobody else besides the people who actually gather the data, know how to analyse it.”

“Originally, sometimes, they were written for microbes (for instance). And so people working on plants or animals were interpreting as they wanted and it makes them very heterogeneous in the end on the dataset.”

- The Digital Divide refers to the risk that OS, in a counterintuitive manner, would favour wealthier countries and institutions, or ones that already have some advantage over others. This challenge affects all the previous challenges related to the FAIR principles. Imbalance of resources between countries and between institutions or even people in the same country may challenge a genuine open access, as well as findability, interoperability and reuse of open data. High-quality data may not be accessible for all, or intelligible or usable to all in an equal manner. Less privileged institutions may not have the tools, resources and/or skills to use open data. A need to make OS more inclusive has been underlined.

“If you have metadata that, for instance, contains references on specific lab equipment that is used to create that data, and then one is state-of-the-art and another is not seen as state-of-the-art, then this devalues the data automatically through the metadata, and it's again a question of resources that some have and some don’t.”

“I was just thinking about […], you know, partnerships that you have within Europe... Do they tend to be, you know […] researchers from resource-rich institutions or do you feel that that's really that your resources so therefore anyone to use […], also from resource-poor areas.”

[1] All quotes provide from the discussions in the workshops.

[2] Translated in English by the authors of the report.

[4] Research papers may be considered as data, especially for Humanities and social sciences.

[5] Translated in English by the authors of the report.

This passage is part of D6.2: Final analysis and mapping of existing European and national OS infrastructures with regard to promoting responsible OS written by Carole Chapin, Nathalie Voarino.